We’ve never lacked for stories about rich people behaving badly — or, just generally, for stories about rich people doing about anything. Most of our stories are about the very rich, especially the ones that are not ostensibly about class at all — the median income of the average American protagonist is way above that of the average American. If it were otherwise, the vast majority of television and film plots would simply be about paying the bills and getting out of debt. You never get the scene in, for instance, Avengers: Infinity War where Paul Rudd’s Ant-Man has to awkwardly ask for an advance on whatever an Avenger’s salary is because otherwise he won’t make rent on the first. A lot of this is screenwriter laziness; a sad rich person elicits empathy and human drama, but you can pretty quickly get them on a plane to Paris or a boat to the Caribbean or on a bender along the fanciest stretch of night clubs in Manhattan. Working class Sex and the City would not have had the same vibes.

But today I’m interested in talking about movies (and a television series) that are explicitly about the rich and their richness. Satires. Social critiques. Eat the rich comedies.

Three recent releases inspired this post

First, Mike White’s hugely popular class-satire-cum-murder-mystery White Lotus finished up its second season on HBO last year on December 11th. Twelve days later, Rian Johnson’s Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery arrived on Netflix (after a weird six day theatrical run a month earlier over Thanksgiving, a strategy deserving of its own post) on December 23rd. On that same date, Janus Films’s new 4K restoration of Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game began its American theatrical run at the Film Forum in New York. While all three filmmakers balance class satire against a kind of humanistic ethos, only Renoir was a registered Socialist, and yet, somehow, his film out of the three projects mines the most empathy, the most care, and seems to have the most affection for it’s wealthy characters.

And this is what I’m interested in. When a film has a political or economic perspective — when parody and satire are utilized to critique some element of our material world — what does that mean for the characters in that work of art? Is it the job of a filmmaker to love their characters or to judge their characters? If judgment is withheld, is that a form of endorsement? Is it valuable or is it destructive to use the persuasiveness of film to compel an audience into sympathizing or even empathizing with so-called bad people?

This line of questioning is partly tied to the old peak TV Breaking Bad / Sopranos / Mad Men discourse, over whether spending so much time invested in these bad/complicated/destructive men was a good thing, a bad thing, or a neutral thing — whether these shows excused these men or even encouraged their behavior in the audience. On a deeper level, the root question has something to do with whether film (and art more generally) works on us directly or indirectly.

I’m going to try and stick with transparency as far as my own takes go, but I don’t think any of these are easy questions. Generally speaking, I love films that don’t reconcile contradictions, that look for small or slanted or half-grasped truths in the spaces between irreconcilables. I love movies that manage to have empathy and curiosity for every character, while still not excusing any political or economic violence.

Broadly, I don’t think film is the right medium for explicit political advocacy, and both film and advocacy are best served by keeping them separate from one another. Specifically, Jean Renoir is my favorite filmmaker and The Rules of the Game my favorite film. So that’s where I’m coming from, but I’m not sure I’m right.

Glass Onion as Spectacle

It’s possible a teacher I had in college just made this up, because I can’t find it anywhere online, but there’s apparently a review of James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake in which the reviewer wrote something along the lines of, “reading this book is like solving the world’s most intricate puzzle, only to find nothing deeper than a dessert recipe as the solution.”

With that in mind, let’s start with Rian Johnson’s new film, Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery. I’m a big admirer of Rian Johnson, but I don’t think of him as high art filmmaker or a great independent voice of cinema or anything like that — he represents something else to me. Rian Johnson, to me, is basically akin to Steven Spielberg. He is an expert builder of movies. He’s in full control of how you feel and when you feel it. He puts thoughts in your brain and then surprises or subverts or undercuts those thoughts with precise technical mastery.

I’m convinced that if Rian Johnson had been born thirty years earlier, he’d have been our generation’s Spielberg. Instead, for a lot of reasons, our generation doesn’t get any Spielbergs. We get like Kevin Feige and seven credited writers on every big budget movie. Johnson has written and directed a lot of big budget movies, true (even a Star Wars movie!), but somehow his brand is still outsider, a little auteur, a little indie. Part of that is the shine he gets off of his brilliant wife.

Glass Onion is only Johnson’s fifth film since 2005’s Brick. In the same span of time after Jaws, Spielberg directed thirteen films. It’s a single data point, but it’s also a good summary of how the movie industry has shifted away from individual voices and original stories when it comes to our most expensive and popular movies. Another example would be Ryan Coogler, who since Fruitvale Station nine years ago, has directed exactly three movies, and every single one of them based on extremely popular pre-existing intellectual property.

But, back to Glass Onion. After seeing the Knives Out sequel at the downtown Alamo Drafthouse during its brief theatrical run, I went home and read two reviews back-to-back that I think get at the discourse I’ve been describing. The first review came from A.O. Scott in the Times, and is summed up pretty well with this pull quote:

A pop-culture savant with technique to spare, Johnson approaches the classic detective story with equal measures of breeziness and rigor. The plot twists and loops, stretching logic to the breaking point while making a show of following the rules. I can’t say much about what happens in “Glass Onion” without giving away some surprises, but I can say that some of the pleasure comes from being wrong about what will happen next.

Scott ends his review praising the movie for being able to engage with political hot topics such as COVID and hypocritical tech billionaires while remaining a breezy puzzle — as opposed to “succumbing to howling rage.”

Adam Nayman, writing for The Ringer, has an altogether different lens:

Frankly, there’s better and more trenchant satire to be made about a well-meaning, well-connected filmmaker preaching “disruption” and “smashing the system” in the guise of a $40 million award-season Netflix comedy. As to who’d have the guts to make a movie like that, well, that’s a mystery worthy of Benoit Blanc himself.

Nayman, and I don’t disagree with him necessarily, spends a lot of words noting that the caricatures of the very rich in Glass Onion are common tropes, that the rich people jokes are clichéd jokes, and that the social satire seems mostly aimed at like minded filmgoers ready to hoot and holler at every half-assed dig at the 1%.

But Nayman, and I do disagree with him here, seems to argue that the film’s goal is to advocate for a political position, and hence its success or failure should be judged by how radical and persuasive its political messaging is. The movie lacks political teeth, and hence is suspect of having normie politics, and hence is not very good. The underlying premise, going further here, is that because the film features very rich characters, Johnson better beat the shit out of them in a politically righteous way or else he’s done something toothless.

Since then, Glass Onion has gotten sucked deeper into the polarized political minefield. Ben Sharpiro’s viral twitter rant, which I don’t need to link to, explicitly assumed the whole movie was a woke moralizing effort, a chastisement of the decadent rich haves written by a woke moralizer or some such nonsense. The fact that a certain faction of the right has taken umbrage at the film has further reinforced the notion that the movie should have something more trenchant to say politically. I guess if you just look at the jokes about rich people, this isn’t wrong. But it does seem to miss the movie that was made.

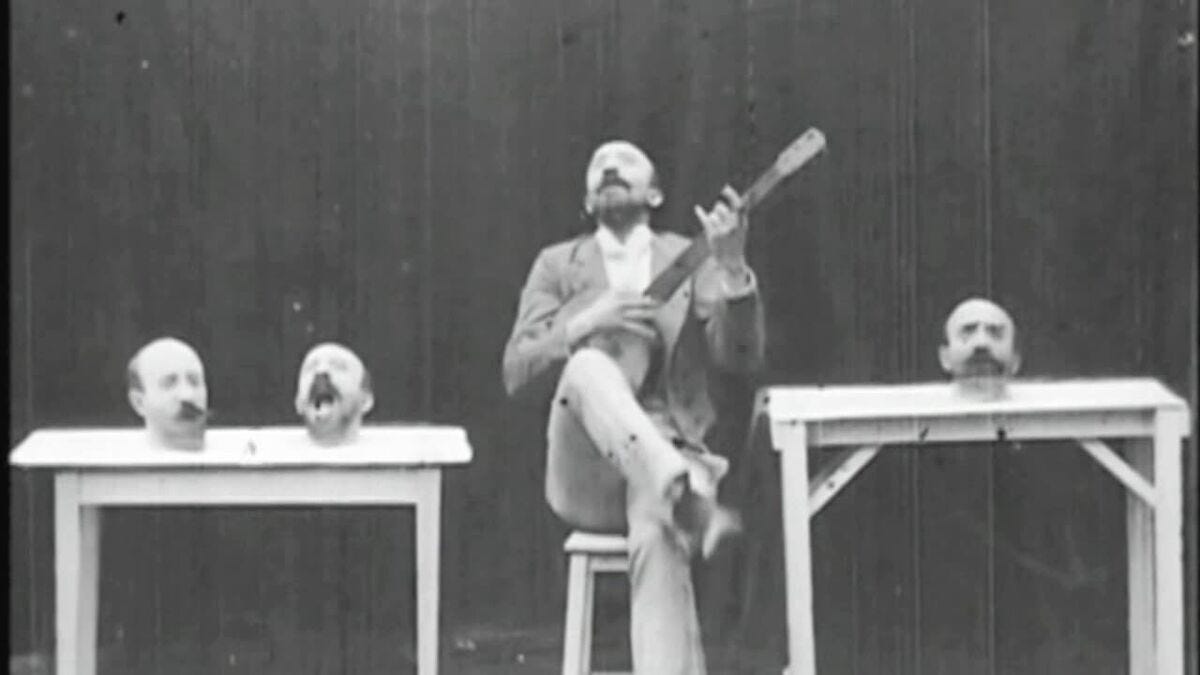

The film theorist Tom Gunning, in his essay The Cinema of Attraction, describes the earliest cinematic arts not as a storytelling medium, but as a spectacle medium. People went to the movies to watch strong men flex, or Annie Oakley shoot plates in the air, or gymnasts contort their bodies. One reel (12 minute or less) films were strung together all afternoon depicting just a series of dope feats.

Georges Meliés, while technically using story to string his parade of spectacles together, was basically just using movie editing and forced perspective to create high tech magic tricks.

Sometimes I see a movie and I think, this is here for the attractions.

Glass Onion is absolutely one of those movies. If we demand of it incisive social critique, beyond what we could find in other mediums, then it falls woefully short. Hell, if we even demand of it the originality of Discrete Charms of the Bourgeosie or The Triangle of Sadness, it’s going to disappoint. But if we ask of it to be an immaculately built puzzle — not just on the page, in the way the mystery structurally unfolds, but in the living images of the cinema, in the way each shot offers layers to un-peel, compositions in depth that reveal more and more clever conceits, editing techniques that ask to be noticed, dissected, misunderstood, and then re-conceived — then it’s a wild success of a movie. Glass Onion is overtly constructed. It feels built, and the pleasure of watching it is in being wrung through the scaffolding of its filmic structure. It is a game, a puzzle, a magic trick, a movie. It has chosen its as its setting a kind of fever dream island of the very rich — but not for that does it exist.

Whose Side is White Lotus on?

The question of Mike White’s White Lotus and its own internal politics regarding class (and sex, and power, and status) is more complicated than Glass Onion, while also being more straightforward. Unlike Rian Johnson’s film, The White Lotus really does thrive in looking directly at class, and does so with originality and detail.

During Season One of the series, Mike White was quoted quite a bit saying that happy endings for the little guy make the audience feel good, but ultimately work as a kind of opiate of the masses — and that he felt like he would be adding to a certain type of self-satisfied stasis to just put another heart lifting story into the world in which the little guys succeeded and the nasty rich guys failed. I love how thorny this idea is. There is a certain audience segment that needs to see bad guys fail, otherwise they assume the movie roots for bad guys. White understands that stuffing our throats full of uplifting happy endings is easy and a little useless. At the same time, he seems to have mellowed on that point somewhat in Season 2, (SPOILERS), especially with Lucia and Mia, who end the final episode in what can only be described as a victory lap.

For as much love as The White Lotus gets, it does get the same type of shit from a ton of different critics. Michelle Goldberg writes,

“No moral framework determined who won and who lost. Tanya, after taking control of her life by shooting the gay aesthetes conspiring with her husband to have her killed, psyched herself up with a girlboss affirmation — “You got this” — then died in the dumbest way possible.”

I guess this is supposed to be a critique, but I don’t understand why. She seems to be complaining about irony as a whole mode, which is picking a pretty big fight.

Nina Metz, a writer for the Chicago Tribune, refers to White Lotus as having nothing to say in a similar vein. Her read is that the show brings up a bunch of interesting problems, but then kicks the tires at the edges instead of really dealing with any them.

John Ganz, a great substack writer, has taken to twitter and essay form regularly to bash the shit out of White Lotus on the grounds that it’s suspiciously complicit and sympathetic with its characters, its critiques seem to be banal and every day, and at times White Lotus seems to take a kind of ironic and dry approach to the damages done by the very rich. In other words, the vibes feel somewhat toothless and complicit (compared to, say, Eisenstein’s Strike in which a scene of industrialists slaughtering striking factory workers is literally intercut with a farmer butchering a pig to death), even if the superstructure is pretty critical. Keep in mind both seasons are built around the very rich brutally committing murder and, especially in the more “radical” season one, getting away with it.

I don’t want to straw man these arguments. The sympathetic way I’d lay them out would be something like: movies are persuasive, they’re fun, they feel like reality, and because of that they are very powerful and work on an unconscious level. Spending lots of time ogling beautiful yachts, and mansions, and seasides, and luxury hotels, and beautiful rich people is inherently problematic because on some level its pleasurable. The class critique is there to satisfy the pundit class, but really you’re getting your cake and eating it too, throwing luxury porn on the screen while still being able to excuse yourself excoriating the rich.

But if we’re looking for the literal outcome of the story to be the radical element of a movie, I do really believe we’re looking in the wrong place.

I’m more interested in a type of radicalism that is at once more humane and also more entertaining. That’s the radicalism of making the audience complicit. Mike White wants us to understand how his characters feel. He wants us to feel for them. In interviews, he is immensely self-critical and self-aware. He gives himself shit for being a white Santa Monica vegan Buddhist screenwriter. But he also owns that he is those things. He’s humble enough to not offer solutions, but his work is in pointing out hypocrisies, cracks in the facade of monoculture, and to finger the sore spots.

This isn’t just a project of humanism or naturalism. It’s sneakier than that. White Lotus at once insists that there is humanity in all of us and also that there is cravenness in humanity. It suggests that we can feel for anybody experiencing a certain kind of pain or loneliness, and in fact asks us to invest a great deal of care into people who have more money than we could ever imagine who are feeling pain and loneliness, but it also suggests, in a sinister way, that we have a lot in common with those would raze the earth.

The Messiness of The Rules of the Game

Which all of this brings us to Jean Renoir’s masterpiece, The Rules of the Game. I feel like a dope, because when I saw the new Janus 4K restoration the other night at Los Feliz Theater in Los Angeles, right as the movie ended, I muttered, “perfect movie.” And then as I was walking out with my wife, I passed a middle-aged woman who turned to her partner and said, “perfect movie.” Then outside, a couple of college-aged cinephiles were talking about “what a perfect movie” it is.

It is a perfect movie. But it is not a clean, or precise, or efficient movie. It’s messy as hell — and part of the thrill is in watching Renoir barely stay in control of mounting chaos. On a behind the scenes production note, all of the exterior scenes and early Parisian scenes went so over time and so over budget, that everything shot at the Chateau, the bulk of the film, was rushed into a hyper condensed shooting schedule. Renoir made the most of long takes and roving cameras, along with impeccable blocking and deep stage framing, to harness that speedy production into something magnificently cinematic.

But the core messiness of The Rules of the Game is not in its technical execution, but in its approach to people. Watch this clip of Renoir talking about his film almost 20 years later. It’s an incredible glimpse at a wry, aging genius.

The key thing he says about the film, though, is

I just wanted to make a movie, even a pleasant movie, but a pleasant movie that would at the same time function as a critique of a society I consider rotten to the core, and which I still consider rotten to the core. Because this society continues in its awfulness and is leading us towards some fine little catastrophes.

You take this notion and put it together with maybe the film’s most famous line, “The awful thing about life is this: everybody has their reasons,” and I think you start to get at the irreconcilable contradictions that Renoir is asking us to sit with.

There’s something incommensurable between the logic of political critique and the act of human empathy. Renoir makes the social critique fairly obvious, especially regarding class — in one of the film’s most famous sequences we just watch as the very rich massacre a field of rabbits and pheasants as their hired help stomp through the wood, banging sticks against trees to create easy targets and fake hunting for the gentry. The life going out of a single rabbit on screen, with a twitch of its leg and then a horrible sagging sigh, is mirrored at the end of the film with the brutal and dumb death of Andre Jurieu. Andre is technically killed by a jealous, working class groundskeeper, a moment foreshadowed earlier when the Marquise mentions offhandedly that he occasionally reads of immigrant laborers killing each other over women, but could never imagine such a thing himself, and that fact drips with a kind of useless irony. Because Andre may have been shot by a groundskeeper, but he was killed by his own class.

I think what Mike White is trying to do in White Lotus is closer to Renoir than it is to Rian Johnsons’s aims — and in many ways that’s why White has received more criticism. Mike White isn’t quite the humanist Renoir is. He’s interested in the way humans use transactional relationships to paper over loneliness, the ways in which communication can break down even between the most connected of families or couples. Mike White is focused on how we are all stuck, to some degree, in our own brain, and the modern world makes it easier and easier to stay that way, to dig deeper, to not connect.

So White is depicting all of that with a sense of empathy. These very rich people may have built their empire on blood, may be destroying the earth and the vast impoverished and laboring classes, may be personally cruel and selfish and manipulative, but Mike White can still see their sadness, their desires, their wanting. And he’s interested in that, too.

Compare that to something Andre Bazin wrote once about Renoir:

“The climate of fraternity which reigned within his company eventually established itself between the film and the spectators, for it was always Renoir's desire to elicit from the public not admiration but a sense of complicity, a friendly connivance quite foreign to the mechanical impersonality of the medium. In this way Renoir's films have something in common with the theater: they demand that we enter into the game.”

So Renoir is the big, romantic lover of life and conviviality and fraternity, who also sees the very rich as leading the world towards catastrophe. Mike White is the anxious, lonely, neurotic who understands human weakness and smallness because he himself feels weak and small. And Rian Johnson is the spectacle maker, the builder of movies whose view on both people and politics comes second to the roller coaster ride of well built genre cinema. All three filmmakers try and balance irreconcilable elements, try to nod to politics without becoming activists, and, most interestingly of all, steadfastly refuse any answers or solutions to the problems they bring up.